|

||

There

are two kinds of light that can blind. There’s the light

of the sun. White hot, it burns out the nerve endings in the

retina. It’s an irreversible and total negation of sight

that, because its effect is catastrophic and ultimate, assumes

a sublime meaning. The naked sun is blinding in a symbolic

sense because its immense energy – hurled in all directions

toward infinity – is purely and simply burning itself

out. The sun squanders its fortune on a cosmic scale, like

a billionaire depleting their wealth through one furious party.

Only absolute authority can waste itself like this, in a spectacle

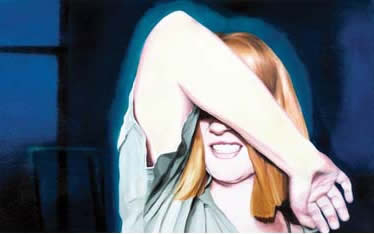

of dissipation in which productivity is identical to annihilation. Stare at the face of a sun-king or a god and their glory (which is the fabulous expenditure of their essence without work, return or profit) will incinerate your sight of them. This hot blindness is the consequence of staring straight into the origin of light (such as the sovereign’s all-seeing eye, as devastating as a nuclear blast). The blindness that results is punishment for transgressing the decorum of vision. To see without the risk of blindness, our vision needs to be deflected. We navigate through the world over which the sun has dominion by looking on reflected light, much like the way Perseus manages to approach the Gorgan (whose direct gaze kills those who look on it) by staring at her mirror image on his shield.  There is another light that blinds. But - unlike the sun’s light – it is cold. Absolutely cold: absolute zero. It doesn’t burn; it stuns, seizes and freezes. Its blinding effect is like a pilot’s white-out in a cloud or snowstorm, or the split-second glare off a windscreen that floods your vision of the street. This is the blindness of an animal immobilised in headlights on a dark road, or it’s the vacant stare of a party guest into the camera’s flashgun, or an epileptic’s arrested gaze at a flickering strobe light. Just as the solar wind disinterestedly irradiates everything, the hot light of glory is indifferent to those it blinds. Like the blindfolded figure of Justice – absolute, pure justice – it is impartial. On the other hand, the cold radiance of the flare or strobe seems intended for its victims, even if it treats them impersonally and appears accidental. Like blind Cupid, its attentions are directed, but erratic. Rather than a brilliant incinerating expenditure of energy, this is a light that coldly seduces and consumes. We see it when we submit to the evil eye, or to the eyes of a mesmerist, the spotlights on police helicopters scanning the streets, or the light rays from flying saucers that immobilise solitary cars and their drivers on country roads. This light incorporates the eyes that look at it, in the way that the Borg – the most feared species in the universe of Star Trek: The Next Generation – incorporates, by a glacial logic of assimilation into its intensive hybrid state, all organic life forms. We are the fuel for this light’s arid appetite. Our sight is abducted by it, and so is flattered by the ravishment. This is what lures us toward it, spellbound like children entranced by the incandescent elegance of angelic extraterrestrials. Our blindness in this case is a sort of seizure, a captivation: a plateau state rather than an annihilating climax. Cold seduction by incorporation is anything but glorious. This, the second type of light, doesn’t come from the sun, nor from any dazzling god or sovereign who illuminates the world. Rather than emanating divine mystery (identified with a prohibition on looking), this light – ungodly, parasitical and dazzlingly superficial – is associated with secrecy and conspiracy and paranoia: with looking everywhere, inside, outside, above and below. It’s a light allied to all those nocturnal phantasms or inhabitants of the twilight zone who challenge, sabotage or undermine solar authority and its devout, autocratic regents on earth. It is the ethereal medium in which ghosts and spooks swarm, like blind bats swirling through the evening sky. It is the voluptuous extinction of the human will and ego, an empty eternity gleaming lethally at the end of a dark tunnel. It silently explodes through windows and from under the doors of research laboratories when a genetic experiment catastrophically mutates. It haemorrhages from the eyes of a drug fiend, like ectoplasm pouring out of a medium in a séance, when they drop the lunatic dose of a psychotropic substance.  It’s under the cover of this blinding light that all things alien seduce and abduct their prey. Poltergeists or other demons use it as an instrument to snatch children from their parents’ arms. Succubi enclose their supplicants or sacrificial victims within it. It is ejaculated by supernatural and superhuman lovers, like the couple at the conclusion of Luc Besson’s movie The Fifth Element whose orgasmic embrace fires, in a volcanic convulsion, a searchlight beam of jism into deep space. In Ron Howard’s Cocoon, a man peers through a hole in a wall to spy on a beautiful girl undressing next door. But the peepshow scene is suddenly flooded with light – blinding, like the original Peeping Tom, both him and the audience – when, having removed her clothes, the young woman continues the striptease and peels off her counterfeit bare human skin. This light, permitting a glimpse of her naked alien body, is hardly the wrath of god, but instead the glare and flush of desire. Alien visitations, out-of-body experiences, hauntings, near-death experiences: these are not incarnations of providential divinity, a singular, absolutist and sublime presence; instead, we consider these supernatural phenomena to be either caused by – or, perhaps, accessed by – derangement. These are sorts of scenes that Lily Hibberd paints for Blinded by the Light: figures approached by, embraced by and succumbing to the incomprehensible passions of their fantastically luminous, otherworldly encounters and visitors. The blinding light that induces these apparitions has to be a travesty of solar light. Not its inverse or negative, but a counterfeit of sunlight. It is a false light, conspiratorial; the vehicle of a theatrical device. And, rather than spiritual illumination or conversion, the blindness it induces suggests intoxication, a narcotic or anaesthetic trance: pure spectatorship. A blind faith in the visible; beguiled, charmed, hallucinatory. It’s what you see when gazing, off your face, at the hypnagogic lightshow in a nightclub. Or when spaced out late at night in front of the tv. Or when taken by surprise by a fluorescent dangling skeleton in a ghost train.  The

blinding light in Hibberd’s paintings is light that

is a special effect. In a word, a light that is “cinematic”.

The spectral events that she paints are all derived from scenes

in science fiction and fantasy cinema: Close Encounters,

Altered States, Fearless, Cocoon, Fifth Element, Ghost and

Poltergeist. Hibberd restages, in suburban homes

and in the studio, those scenes from these movies in which

characters confront a brilliant white light. Using the same

three models for each scene – a woman, man and a baby

– but in different costumes and wigs, she photographs

them doused in a staged version of the lighting effect, and

then paints from that photograph. But these painted scenes

aren’t duplications of the movie scenes. They’re

after-images: manufactured after their cinematic sources,

yet appearing as persistent visions lingering beyond the melodramatic

incidents that provoked them. Another story – a ghosted

story – seems to unfold in consistent wide-screen format

through this series of paintings as Hibberd’s exemplary,

nuclear family is relentlessly haunted, stalked and assailed,

enticed and consumed by an enigmatic force. What Hibberd stages

in these images is a sort of séance, composed in order

to induce a visitation (and consummation) by cinematic light. The

blinding light in Hibberd’s paintings is light that

is a special effect. In a word, a light that is “cinematic”.

The spectral events that she paints are all derived from scenes

in science fiction and fantasy cinema: Close Encounters,

Altered States, Fearless, Cocoon, Fifth Element, Ghost and

Poltergeist. Hibberd restages, in suburban homes

and in the studio, those scenes from these movies in which

characters confront a brilliant white light. Using the same

three models for each scene – a woman, man and a baby

– but in different costumes and wigs, she photographs

them doused in a staged version of the lighting effect, and

then paints from that photograph. But these painted scenes

aren’t duplications of the movie scenes. They’re

after-images: manufactured after their cinematic sources,

yet appearing as persistent visions lingering beyond the melodramatic

incidents that provoked them. Another story – a ghosted

story – seems to unfold in consistent wide-screen format

through this series of paintings as Hibberd’s exemplary,

nuclear family is relentlessly haunted, stalked and assailed,

enticed and consumed by an enigmatic force. What Hibberd stages

in these images is a sort of séance, composed in order

to induce a visitation (and consummation) by cinematic light. Cinema is the phantasm that is summoned in these paintings: but it is a supercinema – the white light of the projector flaring through the screen action, just as a ghost manifests itself in a living room. Is this like the light exposed when a film breaks in the projector, or when a frame jams in the projector gate and melts? Not quite. That’s a revelation of the naked apparatus – the “real” of cinema; shocking, because to view it we must lose sight of the movie we are watching. We must, in other words, ignore the veil of mirages that constitutes the imaginary (or image repertoire) of cinema. What we might call supercinema, on the other hand, is not constituted by a negation or even disavowal of cinematic illusion, but by the hyperbolic affirmation of it. It is an over-exposure of cinema. Like the naked alien’s body in Cocoon illuminated by the superimposition of exhibitionism and voyeurism – supercinema is a body that, as in striptease, converts even naked human skin into a special effect. This cinema is a hallucinatory blur resembling the blank white cinema screen that Hiroshi Sugimoto 1993 repeatedly photographed in drive-in movies and picture palaces, by leaving his shutter open for the entire duration of the feature film. Hibberd’s paintings are, similarly, of an over-exposed cinema, of a bride stripped bare, down to her desirable alien (rather than mechanical) substance. And here comes the bride. A solitary young woman lifts her bare arm across her eyes shielding them from a blinding light. She won’t turn away from it, even as it seems to threaten her; in fact, she seems to be turning toward what she cannot bring herself to look at. Her grimace could equally be a welcoming smile. Even as it bleaches out the colour and detail of her bare skin, this light doesn’t evaporate or dematerialise the body, or bestow an immaterial aura to it. Rather, it incorporates the flesh it lights up, becoming a substance that seems, like icing, to flow and set at once. In the movie from which this image is taken, Ken Russell’s outrageous s-f acid fantasy Altered States, this light is the consummation of a research scientist’s experiment in regression to a primal psychic state – to, as he puts it, the brink of nothingness. What blinds this woman – the scientist’s lover – is the monstrously naked discharge of energy from this horizon of identity, at which the object of desire is visible only as pure psychic affect, as the mirrored intensive state of her passion.  Hibberd

has given this painting the same title, Blinded by the

Light, as the exhibition itself. Evidently, she sees

this as an emblematic image if not the premise for the show.

It is also a climax to the narrative suggestions of the other

paintings since it depicts the only figure that is incapable

of directly looking into the light. The painting also poses

a special relation between the viewer and the subject. Immediately

in front of the figure, the source of this incandescent desire

is the viewer in the gallery … and, in the studio, the

artist herself as she paints the image. The identity of artist

and viewer in this case renders the painting a type of mirror,

of both its own production and its consumption. It is an image,

like the lover’s image in Altered States, at

the brink of nothingness. And the longer you look, the closer

to that event horizon you get. Gradually, every five to ten

minutes, the exhibition lights automatically fade out, leaving

you in the dark with nothing but the after-glow of the phosphorescent

pigment used by Hibberd to paint her blinding light. This

after-image of the exhibition is a phantom, a special effect,

visible only by losing sight of the image, while also being

a false double of that image. The image that we take to be

the real subject of the exhibition is a counterfeit human

skin taken off by an alien body in the dark. And in this darkness,

like the darkness of a cinema, we see the lucid substance

of our own desire to be taken in. Hibberd

has given this painting the same title, Blinded by the

Light, as the exhibition itself. Evidently, she sees

this as an emblematic image if not the premise for the show.

It is also a climax to the narrative suggestions of the other

paintings since it depicts the only figure that is incapable

of directly looking into the light. The painting also poses

a special relation between the viewer and the subject. Immediately

in front of the figure, the source of this incandescent desire

is the viewer in the gallery … and, in the studio, the

artist herself as she paints the image. The identity of artist

and viewer in this case renders the painting a type of mirror,

of both its own production and its consumption. It is an image,

like the lover’s image in Altered States, at

the brink of nothingness. And the longer you look, the closer

to that event horizon you get. Gradually, every five to ten

minutes, the exhibition lights automatically fade out, leaving

you in the dark with nothing but the after-glow of the phosphorescent

pigment used by Hibberd to paint her blinding light. This

after-image of the exhibition is a phantom, a special effect,

visible only by losing sight of the image, while also being

a false double of that image. The image that we take to be

the real subject of the exhibition is a counterfeit human

skin taken off by an alien body in the dark. And in this darkness,

like the darkness of a cinema, we see the lucid substance

of our own desire to be taken in.© Edward Colless 2003 |

||